State v. Yelp

A personal jurisdiction battle in the new 15th Court of Appeals

This summer, the Texas Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of the Fifteenth Court of Appeals, in a lengthy decision by Justice Young. That court is now up and running. It has even released its first opinion. As promised, I’ve got my eye on the court. There are several interesting cases I plan to cover in the next few weeks. The first case, State v. Yelp, is covered in this post. The case presents an interesting personal jurisdiction issue wrapped up in a controversial topic—abortion.

The big question is whether an out-of-state corporation’s registration to do business in Texas subjects it to general personal jurisdiction. In my view, the state overreads the U.S. Supreme Court’s recent decision in Mallory v. Norfolk Southern Railway Co. The statutes at issue in Texas do not include the same express agreement to be subject to general jurisdiction in the state. Nor have businesses had reasonable notice that they would be subject to such sweeping jurisdiction.

A bit of background

In 2009, Yelp registered to do business in Texas. In 2022, a few months after the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Dobbs, Yelp posted a consumer notice on the business pages of every crisis pregnancy center in Texas. The notice said, “This is a Crisis Pregnancy Center. Crisis Pregnancy Centers typically provide limited medical services and may not have licensed medical professionals onsite.” According to the state, the notice painted with an unfairly broad brush—“many crisis pregnancy centers targeted by Yelp do offer a range of medical services provided by licensed medical professionals.” And the message did not convey what Yelp intended—these centers do not provide abortions. Yelp refused to remove the notices for months. Eventually, 24 attorneys general sent a demand letter to Yelp. It amended its consumer notice: “This is a Crisis Pregnancy Center. Crisis Pregnancy Centers do not offer abortions or referrals to abortion providers.” Texas does not object to the new notice.

After an investigation, Texas decided to file suit in Bastrop County district court against Yelp for the original consumer notice, alleging that it violated the Texas Deceptive Trade Practices Act. The state claims that Yelp mislead consumers about the availability of medical services at crisis pregnancy centers. In response, Yelp filed a special appearance challenging the court’s jurisdiction to hear the case. Yelp argues that it is not subject to general personal jurisdiction in Texas because the company is headquartered in and has its principal place of business in California. Texas contends that Yelp, at least implicitly, voluntarily agreed to subject itself to general jurisdiction in Texas when it registered to do business in the state. The trial court dismissed the suit with prejudice, finding Yelp neither consented to general jurisdiction nor did this suit arise out of any contacts with Texas for specific jurisdiction.

The Appeal

On appeal, Texas argues that this case is much like Mallory v. Norfolk Southern Railway Co., decided at the U.S. Supreme Court last year. 600 U.S. 122 (2023). In Mallory, the Supreme Court clarified that its more than one hundred year old decision in Pennsylvania Fire Ins. Co. of Philadelphia v. Gold Issue Mining & Milling Co., 243 U. S. 93 (1917), was still good law. Despite confusion about the impact of intervening decisions like International Shoe, consent to general jurisdiction still exists. Due process does not forbid a state from requiring an out-of-state business to agree to be subject to general personal jurisdiction as a condition of registering to do business in the state. Justice Gorsuch’s plurality provides a succinct background of Pennsylvania Fire:

Pennsylvania Fire was an insurance company incorporated under the laws of Pennsylvania. In 1909, the company executed a contract in Colorado to insure a smelter located near the town of Cripple Creek owned by the Gold Issue Mining & Milling Company, an Arizona corporation. Less than a year later, lightning struck and a fire destroyed the insured facility. When Gold Issue Mining sought to collect on its policy, Pennsylvania Fire refused to pay. So, Gold Issue Mining sued. But it did not sue where the contract was formed (Colorado), or in its home State (Arizona), or even in the insurer’s home State (Pennsylvania). Instead, Gold Issue Mining brought its claim in a Missouri state court. Pennsylvania Fire objected to this choice of forum. It said the Due Process Clause spared it from having to answer in Missouri’s courts a suit with no connection to the State.

600 U.S. at 131–32 (citations omitted). The Missouri Supreme Court upheld consent by registration. Pennsylvania fire turned to the U.S. Supreme Court, which held that Pennsylvania Fire could be sued in Missouri by an out-of-state plaintiff on an out-of-state contract because it had agreed, in an executed and filed power of attorney, to accept service of process in Missouri on any suit as a condition of doing business there. The Supreme Court held that Pennsylvania Fire controlled Mallory. Id. at 134.

Much like the Missouri law at issue in Pennsylvania Fire, the Pennsylvania law at issue in Mallory provided that an out-of-state corporation “may not do business in this Commonwealth until it registers with” the Department of State. 15 Pa. Cons. Stat. §411(a). As part of the registration process, a corporation must identify an “office” it will “continuously maintain” in the Commonwealth. §411(f ); see also §412(a)(5). Upon completing these requirements, the corporation “shall enjoy the same rights and privileges as a domestic entity and shall be subject to the same liabilities, restrictions, duties and penalties . . . imposed on domestic entities.” §402(d). Pennsylvania law is also explicit that “qualification as a foreign corporation” permits the courts to “exercise general personal jurisdiction” over a registered foreign corporation. 42 Pa. Cons. Stat. §5301(a)(2)(i). The Supreme Court concluded that this case fell squarely within Pennsylvania Fire’s rule.

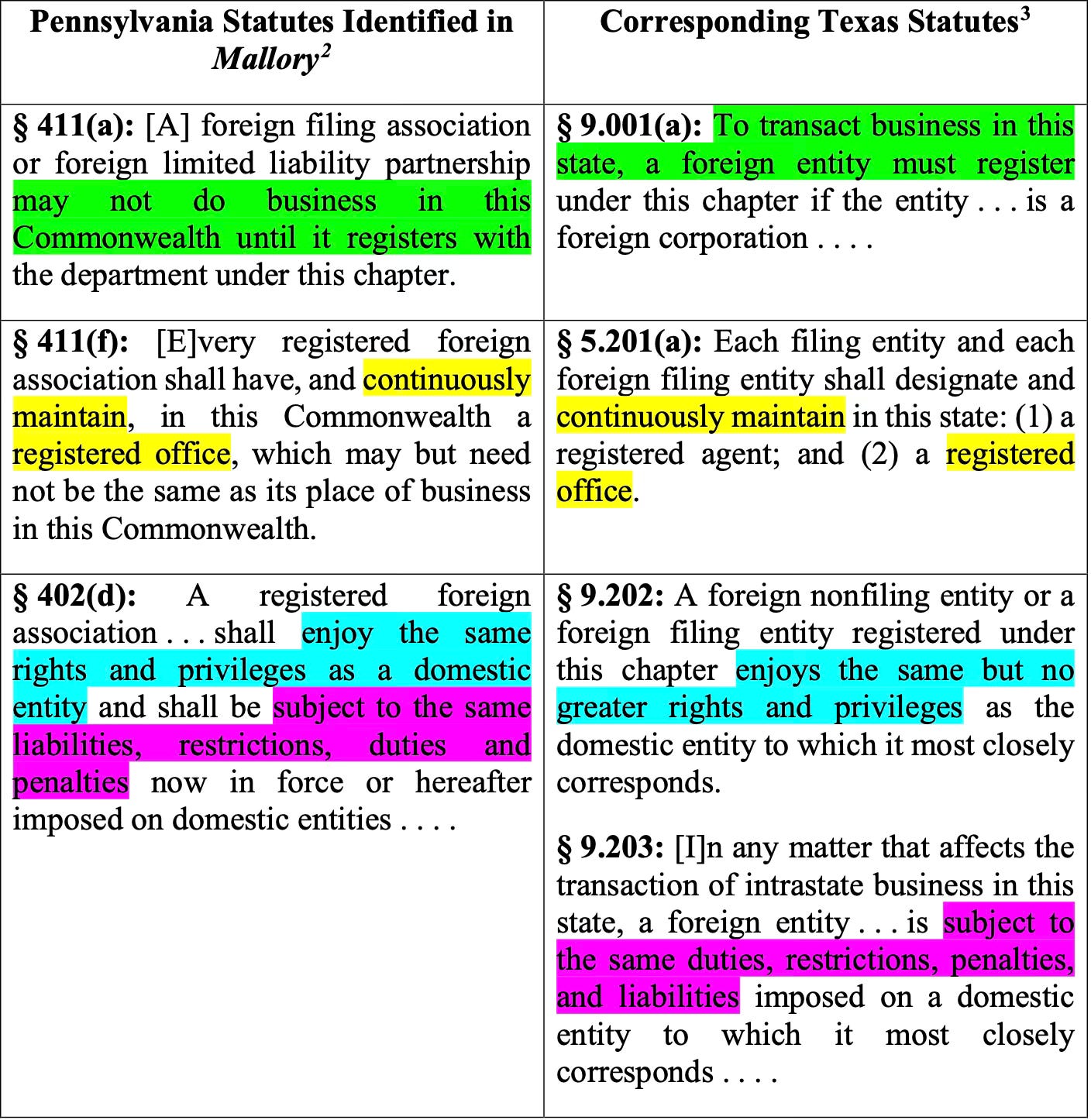

Texas highlights the similarities between the Pennsylvania statute’s language at issue in Mallory and the language in several Texas statutes governing the registration of out-of-state companies:

Op. Br. 16. Yelp rightly focuses on a key difference between the relevant Texas statutes and the Pennsylvania statute not mentioned in the state’s chart—the express consent to general personal jurisdiction in §5301(a)(2)(i). Yelp notes, as the parties did in Mallory, that this is unique among the states. Resp. Br. at 18 n.5. True, others have consent by registration: Georgia has adopted the Pennsylvania Fire approach that registration to do business, without an express jurisdiction provision, subjects parties to general jurisdiction in the state. See Cooper Tire & Rubber Co. v. McCall, 863 S.E.2d 81, 92 (Ga. 2021). The state’s response seems to be to repeat a line from Mallory that the Supreme Court never required a registration statute to contain any magic words to subject the company to general personal jurisdiction. See Op. Br. 14, 17, 20; Reply Br. 2, 7. But several things cut in Yelp’s favor, in my view.

First, the “magic words” colloquy the state relies on is about whether the statute satisfies the consent requirement for due process. It does not obviate the need to have some idea a business is consenting. Justice Barrett, following in the footsteps of her boss Justice Scalia, contends that a sort of implied consent was “purely fictional” and can no longer stand after International Shoe. 600 U.S. at 171–75 (Barrett, J. Dissenting). Voluntary, actual consent is necessary, in Justice Barrett’s view, for consent by registration to satisfy due process. Part II.B of Justice Barrett’s opinion distinguishes actual consent from the sort of fictional consent that was jettisoned after International Shoe. Id. at 175–76. She agrees that no magic words are necessary, but she notes that the Pennsylvania statute at issue in Mallory distinguished between consent and mere registration. See §§5301(a)(2)(i), (ii). To her, that suggests that mere registration is not consent. Id. at 176. The Pennsylvania legislature must have thought they were different or the statute would contain surplusage. And, quoting Judge Learned Hand, Justice Barrett says that without express consent, the “normal rules” of jurisdiction apply. Id. at 179. The majority’s dismissal of this concern as expecting magic words also doesn’t address whether Yelp even impliedly consented to general jurisdiction it had little if any notice it would be subject to.

Second, notice should be given, and as discussed above, is given when a company registers to do business in Pennsylvania. That is, after all, a hallmark of due process. Notice made a difference to the Georgia Supreme Court in evaluating the same issue. For example, in Cooper Tire, the Georgia Supreme Court recognized that its registration statute does not expressly notify out-of-state corporations that obtaining authorization to transact business in the state and maintaining a registered office or registered agent there subjects them to general jurisdiction in Georgia courts (unlike Pennsylvania’s law). 863 S.E.2d at 90. However, the Georgia Supreme Court concluded that its general jurisdiction holding in a previous decision notified out-of-state businesses that their corporate registration will be treated as consent to general personal jurisdiction in Georgia. That distinguishes Georgia from a number of other states, including Missouri. (The Missouri Supreme Court, just ten years after Pennsylvania Fire, reversed course and concluded that its corporate registration statute at issue in Pennsylvania Fire did not amount to consent to general jurisdiction in the state.) As the parties conceded at oral argument in Mallory, Pennsylvania is the only state with a statute explicitly treating registration as sufficient for general jurisdiction. And as Justice Barrett noted, historically, a registered agent in the state was viewed as subjecting a company to jurisdiction for suits arising from activity in the state. 600 U.S. at 173.

The state relies on a few decisions from Houston’s First Court of Appeals in its reply to suggest Texas too has on-point caselaw. See Reply Br. 4. And, according to the state, several other statutes that involve investigations and actions by the attorney general provide the basis for finding consent to general jurisdiction. The state says that, at best, this is an open question. That seems right—SCOTX has never decided the question. But I’d lean to say that Yelp has the better argument, overall.

This will be an interesting case to watch. I’ll keep everyone updated as the case progresses and a decision comes down.